Overhaul of diagnostic bible shrouded in secrecy

It's a tried-and-true formula:

1. Do a quick-and-dirty study or two.

2. Find a huge, perhaps escalating, problem that has heretofore been overlooked.

3. Create a product label (aka diagnosis).

And, voila! The drug companies will take it from there. A diagnosis that was once just a twinkle in the eye of a creative researcher becomes reified as a concrete entity.

Over the past couple of decades, the DSM has risen from its humble origin to an object of worship, regarded as the absolute scientific truth. Privately, however, many mental health professionals refer to it as a "joke." That's partly because we are aware of studies showing the poor validity of many of its constructs. It's also because we know about some of the forces (in addition to scientific progress) that influence each new edition. These include internal turf wars (the DSM-III was developed in large part to decrease the power of the psychoanalytic wing of psychiatry), cultural fads, group-think, and outside lobbying. And leading the outside lobbying, of course, is the pharmaceutical industry.

An example of how this process works is the case of shyness. Christopher Lane, an English professor and Guggenheim fellow, shows in his book,

Shyness: How Normal Behavior Became a Sickness, how psychiatrists transformed shyness from a normal personality trait into a pathological condition labeled Social Anxiety Disorder. As Lane points out, not only can diagnoses be manufactured out of whole cloth, but their prevalence can be made to rise and fall like the stock market through arbitrary adjustments of the threshold cutoffs. And the DSM has a very low bar for calling something a disorder.

In writing his book, Lane was able to get unprecedented access to internal memos and letters of the American Psychiatric Association's DSM-III task force. Based on these primary sources, he credits the rise of the DSM from an obscure tract used mainly by state hospital hacks to an international bible to one man -

Robert Spitzer - who chaired the task force and handpicked its members from people he considered "kindred spirits." (Spitzer is perhaps better known among the general public for his controversial stance that gay people could be turned heterosexual through reparative therapy.)

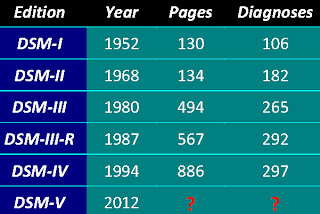

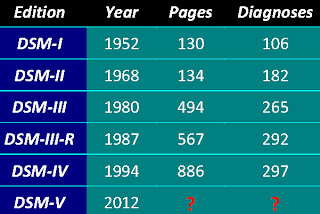

Over the years, the DSM has expanded from just 106 pages to its current 886. (See chart.) The severe mental disorders that once formed the book's core are still in there. There's just so much fluff that it's harder to find them.

And now, the American Psychiatric Association is at it again, working on the fifth edition that is set to launch in May 2012. But this time, perhaps in response to exposes such as Lane's, there will be no telltale memos and letters to document the process. Task force members are sworn to complete secrecy; they must sign a "confidentiality agreement" prohibiting them from disclosing anything to anyone.

Petition drive against secrecyIronically, even DSM-III architect Robert Spitzer is being excluded this time around. Denied access to task force committee minutes and other information, an angry Spitzer wrote a protest editorial that was rejected for publication by the

American Journal of Psychiatry, the official journal of the American Psychiatric Association. (The editorial, "Developing DSM-V in Secret," is online

here). With psychologist Scott Lilienfeld and others, Spitzer last month called for a petition drive to force the APA to open up the DSM-V revision process to public observation.

No doubt hoping to forestall such a petition drive, the APA just announced that its Assembly of local branch representatives will vote November 18 on an "action paper" that would encourage less secrecy. The vaguely worded paper calls on the APA's Board of Trustees to "develop policies and processes that balance the need for openness and transparency and the need to protect its intellectual property." If approved by the Assembly, the action paper will go before the association's Board of Trustees in December.

The secrecy issue comes amid mounting controversy over psychiatrists' ties to the drug industry. The U.S. Senate Finance Committee has launched an investigation into whether drug money is compromising the integrity of medical science. Prominent psychiatrist

Charles Nemeroff of Emory University, whom critics have nicknamed "Dr. Bling Bling," is at the center of the probe; he reportedly earned millions of dollars from pharmaceutical companies while promoting drugs to heal depression and other emotional problems. (See Sunday's

Atlanta Journal-Constitution.)

Perhaps all of this hubbub will encourage the DSM developers to be a bit more circumspect with new diagnoses, realizing that a massively overmedicated and increasingly cynical public could get fed up.

Perhaps the DSM's stranglehold on diagnosis would not be so serious if the book were only being used for its original and stated purpose, as a tool to help clinicians speak the same language in their efforts to understand and treat the mentally ill. But, increasingly, both medical and psychiatric disorders are being shaped by and for the pharmaceutical industry. (A good example of Big Pharma's influence over medical doctors is

The rise of Viagra: How the little blue pill changed sex in America.) And in the forensic arena, the DSM is often employed pretextually, to accomplish various legal outcomes.

Proposed new diagnosesSo, what is in store this time around? Here's my sampling of some of the more controversial changes and new conditions being proposed, some with very specific relevance to forensic practice:

Parental Alienation Syndrome: This is by far the most controversial theory in high-conflict child custody litigation. And the battle lines are drawn primarily by gender: PAS is apt to be the first line of defense when a husband is accused in a custody battle of sexually abusing his children. Despite its lack of empirical support, a partisan lobby is pushing for its inclusion. (See my March 2008 blog post, "

Showdown looming over controversial theory," for more background.)

Hebephilia: All psychodiagnoses, even those of psychotic disorders, have serious conceptual validity problems, but none are weaker than some of those being used to justify the civil commitment of sexually violent predators. The latest, and most farcical, is "hebephilia," or the sexual attraction to teens, which is being aggressively marketed by a small advocacy group. (I'll have more to say about this newly proposed diagnosis very soon; for now, you can check out my Halloween 2007 post, "

Invasion of the hebephile hunters.")

Gender Identity Disorder: The proposed inclusion of this category has drawn the most fire, primarily from transgender activists, who have mounted a petition drive against Ken Zucker, chair of the sexual disorders task force. Information on this controversy can be found

here,

here, and

here.

Among other novel constructs proposed for inclusion in the DSM-V are

Internet Addiction and

Relationship Disorder. If Big Pharma has its way, Female Sexual Dysfunction (FSD) could also be a contender (see my Amazon review of

The Rise of Viagra). In addition, there are proposals to tweak the

criteria for existing diagnoses relevant to forensic practice, including the sexual Paraphilias, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and

Conduct Disorder.

For more information see:

Robert Spitzer’s documents criticizing the DSM-V secrecy (online here)

The APA’s official DSM-V website (here)

A critical analysis of psychodiagnosis more broadly (here)

My review of Christopher Lane's book, Shyness: How Normal Behavior Became a Sickness, is here. (As always, I encourage my readers and subscribers to click on the "yes" button if you find my Amazon reviews helpful; it helps get the word out.)

For further information on the pharmaceutical industry's role in the process, see my May 2008 blog post, "Who will write the next DSM?" and also check out my Amazon booklist, "Psychiatry and science: Critical perspectives."

Other academic articles on DSM diagnosis (not all of them available online, unfortunately) include:

Andreasen, N.C. (2007). DSM and the death of phenomenology in America: An example of unintended consequences. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 33, 108-112

Cunningham, M.D., & Reidy, T.J. (1998). Antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy: Diagnostic dilemmas in classifying patterns of antisocial behavior in sentencing evaluations. 16, 333-351.

Healy, D. Apr 15, 2006. The myth of 'mood stabilising' drugs. New Scientist (David Healy is a very controversial figure in this debate; Google his name for more on him)

Ruocco, A. (2005). Reevaluating the distinction between Axis I and Axis II disorders: The case of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61, 1509-1523

Stevens, G.F. (1993). Applying the Diagnosis Antisocial Personality to Imprisoned Offenders: Looking for Hay in a Haystack. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 19, 1-26

Tom Zander, Psy.D. (2005) Civil commitment without psychosis: The law's reliance on the weakest links in psychodiagnosis. Journal of Sex Offender Civil Commitment: Science and the Law (online here)

The photo of the DSM manuals is from the Bonkers Institute for Nearly Genuine Research, a very creative website.

So begins a Los Angeles Times opinion piece by Jim Trainum, a Washington DC police detective who runs a cold case unit and lectures on interrogations and false confessions and other police investigation topics.

So begins a Los Angeles Times opinion piece by Jim Trainum, a Washington DC police detective who runs a cold case unit and lectures on interrogations and false confessions and other police investigation topics.