|

| Housing unit at Vacaville |

So a lawsuit brought by a California psychologist against the Department of Corrections for alleged harassment of sexual minority prisoners is both rare and potentially groundbreaking.

Lori Jespersen, who identifies as “an openly genderqueer lesbian,” states that she was harassed and ostracized after she began blowing the whistle on rampant mistreatment of transgender and gay prisoners at the California Medical Facility at Vacaville.

Examples of prisoner abuse alleged in her lawsuit, filed this week in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of California, included an instance in which three prison employees “outed” one of Dr. Jespersen's transgender patients on Facebook, providing the prisoner's name and location, identifying her as a mental health patient, and referring to her as “he/she” and “that thing.”

In another alleged incident, a prison employee left a door unlocked while a gay prisoner of color was showering, enabling another prisoner who had been assaulting sexual minority prisoners to enter the shower and assault him. When Dr. Jespersen filed a report under the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA), she says it was never investigated.

Dr. Jespersen alleges that due to her efforts to call attention to the abuse of LBGT prisoners, she was subjected to constant name-calling and threats of violence, including being locked alone on a housing unit with dangerous rapists. She stated the harassment caused her anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance and weight gain, and that she now “lives in constant fear of violence and harassment at work and at home.”

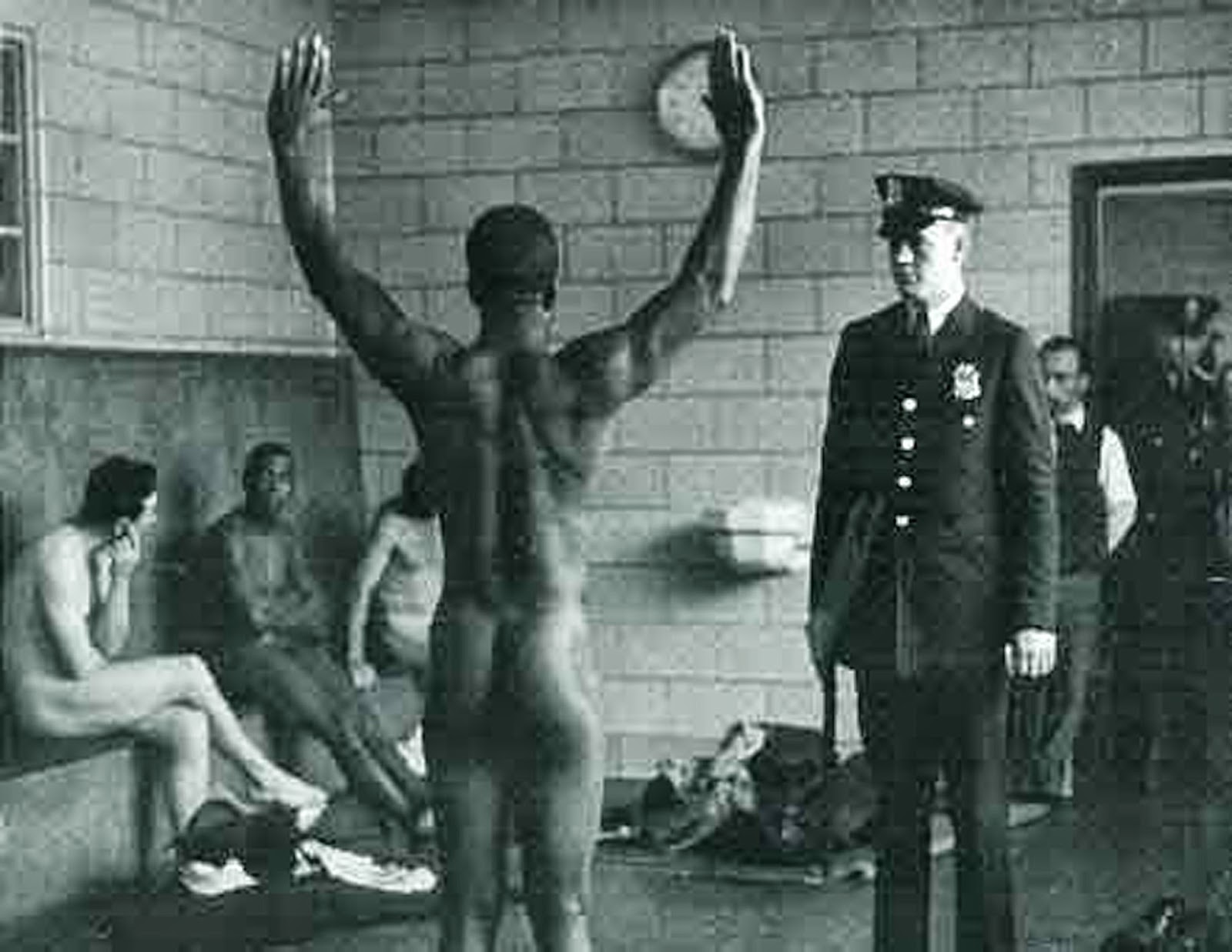

|

| Transgender prisoner at Vacaville |

No safe haven?

If true, her allegations are especially disturbing in that Vacaville has long been regarded as a haven for transgender prisoners. In 1999, during the height of the AIDS epidemic, it became one of only two prisons in the country with specialized medical services for trans prisoners, the majority of whom were infected with HIV.

Dr. Jespersen’s attorney, Jennifer Orthwein, a former forensic psychologist whose practice focuses on gender and sexual orientation discrimination, said that the main goal of the lawsuit is to bring attention to the issue of systemic discrimination, in order to compel a cultural change.

“This case really has the potential to shine a spotlight on what is the key barrier to making progress to protecting vulnerable inmates in these facilities,” echoed Shannon Minter, the legal director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights, in an interview with public radio’s The California Report, “and that is this prison culture of silence and retaliation.”

|

| Trans prisoner at CDCR, UC Irvine study |

Allegations of prisoner mistreatment are not new for California’s massive prison system, which has been under federal oversight for more than a decade due to chronic shortcomings in the treatment of mentally ill and low-functioning prisoners.

The lawsuit also comes at the same moment as a major power shift in the direction of the California Medical Facility. Under the state’s 2017-2018 budget, the intensive 24-hour inpatient psychiatric program at Vacaville and two other prisons has been shifted from the Department of State Hospitals to the Department of Corrections, which has been awarded an extra $254 million and nearly 2,000 new jobs to run them. The shift has caused consternation among mental health personnel, who worry about the quality of psychiatric care and the potential for increased suicides under CDCR management.

Prison psychologist awarded $1 million over racial bias

Although it is rare for prison psychologists to engage in whistle-blowing or file lawsuits, the last time such a case went to trial, the jury awarded the psychologist $945,480 in damages for racial discrimination, a judgment that was upheld unanimously on appeal.

That case was especially disturbing, in that by all accounts Terralyn Renfro was a highly dedicated clinician who went above and beyond her formal duties in her desire to rehabilitate the men in the California prisons where she worked as a contract psychologist. Indeed, it was her very zeal that apparently cost her her career.

According to testimony at her trial, her supervisors did not approve of her attempts to facilitate prisoner self-help groups. They were especially upset that she had set up a self-help library, which became very popular with prisoners at Mule Creek State Prison in Ione.

The manner of Dr. Renfro's firing was humiliating. Without warning, a prison bureaucrat walked up to her one day and handed her a termination notice giving her 75 minutes to leave the prison or be physically ousted by guards. He stayed by her side and escorted her out the gates and to her car. A “DO NOT HIRE” note was placed in her file, so she was repeatedly rejected for jobs at other state prisons. No one ever explained who placed the note, or why.

The Third District appellate court upheld the jury’s nearly $1 million verdict against the prison system for racial discrimination in the firing. Dr. Renfro was the only African American psychologist at Mule Creek Prison at the time.

“Discrimination does not always present as in a scene from To Kill a Mockingbird or The Birth of a Nation,” the appellate court noted. “Even the most racially intolerant manager will often appreciate the need for circumspection, so smoking guns are rarely found.... [T]he jury drew a reasonable inference of discrimination from a pattern of deception, obfuscation, and mistreatment.”

But from the information in the record, the larger impetus for Dr. Renfro’s firing was her zealousness in prioritizing the interests of the prisoners in her care over those of the bureaucrats to whom she reported. The same behavior, perhaps, of which Dr. Jespersen may ultimately be deemed guilty.

* * * * *

The complaint in Jespersen vs. CDCR is online HERE. The appellate opinion in Renfro vs. CDCR is HERE.