The Supreme Court's 2002 decision in Atkins v. Virginia and 2005 decision in Roper v. Simmons marked a significant new direction in Eighth Amendment jurisprudence. This Article explores the Court's emerging conception of proportionality under the Eighth Amendment, which also is reflected in its 2008 decision in Kennedy v. Louisiana. The Article analyzes the application of this emerging approach in the context of severe mental illness. It argues that the Court can extend Atkins and Roper to severe mental illness even in the absence of a legislative trend away from using the death penalty in this context. The strong parallels between severe mental illness at the time of the offense and mental retardation and juvenile status make such an extension of the Eighth Amendment appropriate.A pdf of the full paper is available for online download here.

Severe mental illness would not justify a categorical exemption from the death penalty; rather, a determination would need to be made on a case-by-case basis. The major mental disorders, like schizophrenia, major depression, and bipolar disorder, could qualify in appropriate cases, but not antisocial personality disorder, pedophilia, and voluntary intoxication. The Article discusses the functional standard that should be used in this context, and proposes that the determination be made by the trial judge on a pretrial motion rather than by the capital jury at the penalty phase. Future implications of the Court's emerging approach also are examined.

January 21, 2009

Mental illness: The death penalty frontier

January 5, 2009

New Year’s Briefs – Part I

Happy New Year to all of my loyal subscribers and readers. As usual, a lot is going on and I have had little time to blog. But here are a few highlights, with more to follow.

California strikes draconian sex offender sentence

Imagine serving the rest of your life in prison for missing a bureaucratic deadline. That's what happened to Cecilio Gonzalez under California's three-strikes sentencing law, when he was three months late one year on his annual sex offender registration with the police. Registration infractions usually carry a maximum sentence of three years, and the prosecutor had originally offered Gonzalez a two-year term. He ended up with life because he decided to take the case to trial, acting as his own attorney. That's cruel and unusual punishment, a California appellate court ruled, because the punishment was grossly disproportionate to his "entirely passive, harmless and technical violation of the registration law." It is unclear what effect the ruling may have on other 3-strikes cases, given that California's Supreme Court has declined two challenges by men whose third strikes were shoplifting - in one case videotapes and in another case golf clubs. The L.A. Times has the full story.

Imagine serving the rest of your life in prison for missing a bureaucratic deadline. That's what happened to Cecilio Gonzalez under California's three-strikes sentencing law, when he was three months late one year on his annual sex offender registration with the police. Registration infractions usually carry a maximum sentence of three years, and the prosecutor had originally offered Gonzalez a two-year term. He ended up with life because he decided to take the case to trial, acting as his own attorney. That's cruel and unusual punishment, a California appellate court ruled, because the punishment was grossly disproportionate to his "entirely passive, harmless and technical violation of the registration law." It is unclear what effect the ruling may have on other 3-strikes cases, given that California's Supreme Court has declined two challenges by men whose third strikes were shoplifting - in one case videotapes and in another case golf clubs. The L.A. Times has the full story.Spotlight on violent vets

Veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan who come home and wreak havoc on their communities are a topic of mounting alarm around the United States. In Fort Carson, Colorado, for example, nine combat soldiers have been accused of killing people in the past three years; sexual assault and domestic violence cases are also up sharply. The New York Times has a follow-up story to its initial coverage a year ago, which traced many homicides by combat veterans to war-related trauma and the stress of deployment. As the Times notes, even military leaders are starting to acknowledge that "multiple deployments strain soldiers and families, and can increase the likelihood of problems like excessive drinking, marital strife and post-traumatic stress disorder."

Judges have also noticed the upsurge and in several jurisdictions around the country they are joining with local prosecutors, defense attorneys, and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs officials to set up special veterans-only courts. The judges say trauma-related stress, brain injuries, and substance abuse are contributing to the rash of crimes. They are hoping the innovative courts can help rehabilitate veterans and avoid convictions that might cost veterans their future military benefits, according to a report in the National Law Journal.

Renewed calls for prison reform

With more than 1 in 100 Americans now behind bars, there are additional signs that some policy makers are getting fed up. Driving the trend may be the current economic downturn. As blog guest writer Eric Lotke pointed out last month, and as more and

In prosperous times, state and federal lawmakers wanting to polish their get-tough-on-crime image pass bills putting more people in prison and keeping them longer for offenses such as drunken driving, drug possession and dog fighting. When the economy tanks, those mandatory sentencing laws stay in place, and budget cuts instead dig into drug treatment and job-training programs.Senator Jim Webb of Virginia is getting quite a bit of ink in his vigorous calls for prison reform, and editorials are urging other members of Congress to "show the same courage and rally to the cause."

Perhaps with Barack Obama in the White House, the time will be ripe to reverse course. As we forensic psychologists know, this would be good news for the mentally ill, who make up a large proportion of the millions of Americans behind bars. Indeed, a new study coming out of Texas shows that mentally ill prisoners are not only more likely than others to go to prison, but they are far more likely to recidivate. This "revolving-door" phenomenon owes to a lack of community treatment options, massive downsizing of state hospitals, and a legal system that virtually ignores psychiatric issues. As a result, "many people with serious mental illness move continuously between crisis hospitalization, homelessness, and the criminal justice system," noted the authors of the study, published in this month's American Journal of Psychiatry. The study, "Psychiatric Disorders and Repeat Incarcerations: The Revolving Prison Door," is available upon request from lead researcher Jacques Baillargeon of the Department of Preventive Medicine and Community Health at the University of Texas.

October 13, 2008

DSM makeover: What will they come up with next?

It's a tried-and-true formula:

1. Do a quick-and-dirty study or two.And, voila! The drug companies will take it from there. A diagnosis that was once just a twinkle in the eye of a creative researcher becomes reified as a concrete entity.

2. Find a huge, perhaps escalating, problem that has heretofore been overlooked.

3. Create a product label (aka diagnosis).

Over the past couple of decades, the DSM has risen from its humble origin to an object of worship, regarded as the absolute scientific truth. Privately, however, many mental health professionals refer to it as a "joke." That's partly because we are aware of studies showing the poor validity of many of its constructs. It's also because we know about some of the forces (in addition to scientific progress) that influence each new edition. These include internal turf wars (the DSM-III was developed in large part to decrease the power of the psychoanalytic wing of psychiatry), cultural fads, group-think, and outside lobbying. And leading the outside lobbying, of course, is the pharmaceutical industry.

Over the past couple of decades, the DSM has risen from its humble origin to an object of worship, regarded as the absolute scientific truth. Privately, however, many mental health professionals refer to it as a "joke." That's partly because we are aware of studies showing the poor validity of many of its constructs. It's also because we know about some of the forces (in addition to scientific progress) that influence each new edition. These include internal turf wars (the DSM-III was developed in large part to decrease the power of the psychoanalytic wing of psychiatry), cultural fads, group-think, and outside lobbying. And leading the outside lobbying, of course, is the pharmaceutical industry.An example of how this process works is the case of shyness. Christopher Lane, an English professor and Guggenheim fellow, shows in his book, Shyness: How Normal Behavior Became a Sickness, how psychiatrists transformed shyness from a normal personality trait into a pathological condition labeled Social Anxiety Disorder. As Lane points out, not only can diagnoses be manufactured out of whole cloth, but their prevalence can be made to rise and fall like the stock market through arbitrary adjustments of the threshold cutoffs. And the DSM has a very low bar for calling something a disorder.

In writing his book, Lane was able to get unprecedented access to internal memos and letters of the American Psychiatric Association's DSM-III task force. Based on these primary sources, he credits the rise of the DSM from an obscure tract used mainly by state hospital hacks to an international bible to one man - Robert Spitzer - who chaired the task force and handpicked its members from people he considered "kindred spirits." (Spitzer is perhaps better known among the general public for his controversial stance that gay people could be turned heterosexual through reparative therapy.)

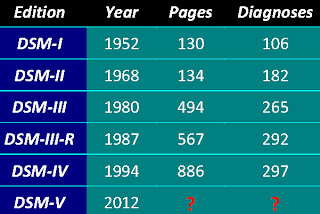

Over the years, the DSM has expanded from just 106 pages to its current 886. (See chart.) The severe mental disorders that once formed the book's core are still in there. There's just so much fluff that it's harder to find them.

Over the years, the DSM has expanded from just 106 pages to its current 886. (See chart.) The severe mental disorders that once formed the book's core are still in there. There's just so much fluff that it's harder to find them.And now, the American Psychiatric Association is at it again, working on the fifth edition that is set to launch in May 2012. But this time, perhaps in response to exposes such as Lane's, there will be no telltale memos and letters to document the process. Task force members are sworn to complete secrecy; they must sign a "confidentiality agreement" prohibiting them from disclosing anything to anyone.

Petition drive against secrecy

Ironically, even DSM-III architect Robert Spitzer is being excluded this time around. Denied access to task force committee minutes and other information, an angry Spitzer wrote a protest editorial that was rejected for publication by the American Journal of Psychiatry, the official journal of the American Psychiatric Association. (The editorial, "Developing DSM-V in Secret," is online here). With psychologist Scott Lilienfeld and others, Spitzer last month called for a petition drive to force the APA to open up the DSM-V revision process to public observation.

No doubt hoping to forestall such a petition drive, the APA just announced that its Assembly of local branch representatives will vote November 18 on an "action paper" that would encourage less secrecy. The vaguely worded paper calls on the APA's Board of Trustees to "develop policies and processes that balance the need for openness and transparency and the need to protect its intellectual property." If approved by the Assembly, the action paper will go before the association's Board of Trustees in December.

The secrecy issue comes amid mounting controversy over psychiatrists' ties to the drug industry. The U.S. Senate Finance Committee has launched an investigation into whether drug money is compromising the integrity of medical science. Prominent psychiatrist Charles Nemeroff of Emory University, whom critics have nicknamed "Dr. Bling Bling," is at the center of the probe; he reportedly earned millions of dollars from pharmaceutical companies while promoting drugs to heal depression and other emotional problems. (See Sunday's Atlanta Journal-Constitution.)

Perhaps all of this hubbub will encourage the DSM developers to be a bit more circumspect with new diagnoses, realizing that a massively overmedicated and increasingly cynical public could get fed up.

Perhaps the DSM's stranglehold on diagnosis would not be so serious if the book were only being used for its original and stated purpose, as a tool to help clinicians speak the same language in their efforts to understand and treat the mentally ill. But, increasingly, both medical and psychiatric disorders are being shaped by and for the pharmaceutical industry. (A good example of Big Pharma's influence over medical doctors is The rise of Viagra: How the little blue pill changed sex in America.) And in the forensic arena, the DSM is often employed pretextually, to accomplish various legal outcomes.

Proposed new diagnoses

So, what is in store this time around? Here's my sampling of some of the more controversial changes and new conditions being proposed, some with very specific relevance to forensic practice:

Parental Alienation Syndrome: This is by far the most controversial theory in high-conflict child custody litigation. And the battle lines are drawn primarily by gender: PAS is apt to be the first line of defense when a husband is accused in a custody battle of sexually abusing his children. Despite its lack of empirical support, a partisan lobby is pushing for its inclusion. (See my March 2008 blog post, "Showdown looming over controversial theory," for more background.)

Hebephilia: All psychodiagnoses, even those of psychotic disorders, have serious conceptual validity problems, but none are weaker than some of those being used to justify the civil commitment of sexually violent predators. The latest, and most farcical, is "hebephilia," or the sexual attraction to teens, which is being aggressively marketed by a small advocacy group. (I'll have more to say about this newly proposed diagnosis very soon; for now, you can check out my Halloween 2007 post, "Invasion of the hebephile hunters.")

Gender Identity Disorder: The proposed inclusion of this category has drawn the most fire, primarily from transgender activists, who have mounted a petition drive against Ken Zucker, chair of the sexual disorders task force. Information on this controversy can be found here, here, and here.

Among other novel constructs proposed for inclusion in the DSM-V are Internet Addiction and Relationship Disorder. If Big Pharma has its way, Female Sexual Dysfunction (FSD) could also be a contender (see my Amazon review of The Rise of Viagra). In addition, there are proposals to tweak the criteria for existing diagnoses relevant to forensic practice, including the sexual Paraphilias, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Conduct Disorder.

For more information see:

Robert Spitzer’s documents criticizing the DSM-V secrecy (online here)

The APA’s official DSM-V website (here)

A critical analysis of psychodiagnosis more broadly (here)

My review of Christopher Lane's book, Shyness: How Normal Behavior Became a Sickness, is here. (As always, I encourage my readers and subscribers to click on the "yes" button if you find my Amazon reviews helpful; it helps get the word out.)

For further information on the pharmaceutical industry's role in the process, see my May 2008 blog post, "Who will write the next DSM?" and also check out my Amazon booklist, "Psychiatry and science: Critical perspectives."

Other academic articles on DSM diagnosis (not all of them available online, unfortunately) include:

Andreasen, N.C. (2007). DSM and the death of phenomenology in America: An example of unintended consequences. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 33, 108-112

Cunningham, M.D., & Reidy, T.J. (1998). Antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy: Diagnostic dilemmas in classifying patterns of antisocial behavior in sentencing evaluations. 16, 333-351.

Healy, D. Apr 15, 2006. The myth of 'mood stabilising' drugs. New Scientist (David Healy is a very controversial figure in this debate; Google his name for more on him)

Ruocco, A. (2005). Reevaluating the distinction between Axis I and Axis II disorders: The case of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61, 1509-1523

Stevens, G.F. (1993). Applying the Diagnosis Antisocial Personality to Imprisoned Offenders: Looking for Hay in a Haystack. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 19, 1-26

Tom Zander, Psy.D. (2005) Civil commitment without psychosis: The law's reliance on the weakest links in psychodiagnosis. Journal of Sex Offender Civil Commitment: Science and the Law (online here)

August 19, 2008

News headlines from around the U.S.

CSI counterpoint

The fallability of forensic sciences is gaining attention lately. Roger Koppl, director of the Institute for Forensic Science Administration, and Dan Krane, a biological sciences prof at Wright State, co-authored this informative op-ed piece in the Newark (NJ) Star-Ledger:

When patients kill

It is always bad news when someone is certified ready for release from a psychiatric hospital and then commits a violent offense. Take William Bruce: Two months after the 24-year-old schizophrenic was released from a hospital in Maine, he hatcheted his mother to death. Here, the Wall Street Journal finds fault with patients rights' advocates who lobbied for Bruce's release:

Christian Science Monitor slams sex offender laws

As public awareness mounts regarding restrictive residency laws targeting sex offenders, the Christian Science Monitor joins the fray with this hard-hitting editorial by C. Alexander Evans:

MoJo's "Slammed: The coming prison meltdown"

And if you've got time for still more reading, a highly recommend the Mother Jones special on incarceration, "SLAMMED." It features at least nine interesting articles, among them:

Not to mention, a "MoJo Prison Guide" with a glossary of prison slang and answers to such obscure prison trivia as:

August 11, 2008

N.Y. Law School offering online courses

Professor Michael Perlin, a preeminent scholar in the field of psychology-law and author of an excellent new book on competency, is announcing an exciting array of online, distance learning courses this fall through the New York Law School.

"Courses combine streaming videos, readings, weekly synchronous chat rooms (meaning, class meets at 8:45 on Monday night, say, but you can be home in your pajamas or at a coffee shop, not in Room A 602), asynchronous message boards and two full day live face-to-face seminars (in which skills issues are always emphasized)," says Perlin.

The four courses being offered this fall are:

- Survey of Mental Disability Law (Monday, 8:45-10 pm)

- Sex Offenders (Tuesday, 8:45-10 pm)

- Therapeutic Jurisprudence (Wednesday, 8:45-10 pm)

- Americans with Disabilities Act: Law, Policy and Procedure (Thursday, 8:45-10 pm)

More information on the online program in mental disability law, including registration information, is here. You can also directly email Liane Bass, Esq., senior administrator of the program.

June 20, 2008

How will Edwards affect competency evaluations?

You have no money or family resources. You are arrested for a serious crime you did not commit. You are assigned an overworked and inexperienced lawyer. You repeatedly call his office, but he is never there. On the eve of trial, he briefly visits you at the jail. He is not familiar with your case. He has done no investigation. He brushes aside your claims of innocence and urges you to plead guilty. You talk to other prisoners. They say this attorney is notorious for falling asleep during trials. Frantic, you ask the judge for a different lawyer. He refuses.

This situation is far from fantasy. The quality of court-appointed counsel is abysmal in many jurisdictions. Indigent defense agencies are understaffed and underfunded, creating a pressing demand to extract guilty pleas from their clients. Appellate courts have consistently ruled that inexperience, falling asleep, and heavy drinking do not necessarily constitute ineffective assistance of counsel.

Your choices: (1) Watch this inept attorney railroad you to prison, (2) plead guilty to a crime you did not commit, or (3) represent yourself.

That latter choice may be your best option. According to the only empirical study to date, pro se defendants were more likely to win acquittals than were defendants with attorneys. Of course, only a tiny proportion of defendants, about 0.3% to 0.5%, represent themselves, often when they are backed into a corner as in the above vignette.

So how does this relate to yesterday's U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Indiana v. Edwards?

In Edwards, the high court carved out a special niche for mentally ill defendants, subordinating autonomy for ostensible fairness. The ruling establishes two levels of competency: the current (low) level for competency to stand trial, and a higher one for competency to represent oneself. But it provides no guidance on what this higher level is.

Although only a small proportion of pro se defendants are mentally ill, a request to represent oneself is likely to trigger a competency evaluation. Indeed, of the 22% of pro se defendants who were screened for competency in the above-cited study by law professor Erica Hashimoto, most (59%) were screened only after they sought to dismiss their counsel. Judges and prosecutors are likely to seek such evaluations because failure to do so might cause a conviction to be overturned.

Expansion of parens patriae doctrine

The underlying problem is that the standard for competency to stand trial is very low, and the courts have consistently refused to raise the bar. But how many judges want an inexperienced, potentially disruptive defendant mucking up their courtroom? So, my prediction is that mentally ill defendants will be found competent, but forced to accept an attorney - and a defense - that they may not want.

Indeed, this was at the crux of Justice Antonin Scalia's lengthy dissent:

"Once the right of self-representation for the mentally ill is a sometime thing, trial judges will have every incentive to make their lives easier … by appointing knowledgeable and literate counsel."

And since the U.S. trial system gives "full authority" to the attorney to conduct the defense as he or she sees fit, a defendant who has not consented to legal representation is stripped of the right to present his own defense.

"The facts of this case illustrate this point with the utmost clarity," Scalia wrote. "Edwards wished to take a self-defense case to the jury. His counsel preferred a defense that focused on lack of intent. Having been denied the right to conduct his own defense, Edwards was convicted without having the opportunity to present to the jury the grounds he believed supported his innocence."

The other side of this argument, of course, is that allowing floridly psychotic defendants to represent themselves sanctions court-assisted suicide in that conviction is almost always assured. This is especially so in serious cases, including death penalty cases.

As the high court held in the half-century-old case of Massey v. Moore, "No trial can be fair that leaves the defense to a man who is insane, unaided by counsel, and who by reason of his mental condition stands helpless and alone before the court."

Slippery slope

As Scalia noted, the Edwards ruling is "extraordinarily vague." It leaves unanswered the question of what level of competence is sufficient to represent oneself, and how that decision will be made.

It also leaves unclear what happens when a defendant has an attorney, but seeks to testify at trial. Will there be an intermediate standard of competency for this situation, in which a certain degree of rational thinking and articulation skills are necessary?

Undoubtedly, the murkiness of the new standard will increase the complexity of these evaluations for forensic psychologists and psychiatrists. This is especially problematic in that court-appointed experts are grossly undercompensated, which attracts inexperienced and poorly trained professionals willing to perform what one attorney I know refers to as "drive-by competency evaluations."

I see the potential of depriving the mentally ill of a right to counsel as a potentially slippery slope. Where does one draw the line? Indeed, in its amicus brief, the American Psychiatric Association noted the need for pro se defendants to have both "oral communication capabilities" and "written-communication abilities."

So, might perceived low intelligence or even low education be a sufficient bar to self-representation? And, how about ideological extremism? Could those labeled "terrorists" be barred from representing themselves in order to air their political beliefs?

This linkage is not a remote possibility, as it turns out. One of the key issues in the Guantanamo prosecutions has been whether the detainees (who are not protected by the U.S. Constitution) will be allowed independent counsel. The initial tribunal rules refused to allow competent detainees to represent themselves. Now, detainees may decline government-appointed lawyers, but the tribune may force counsel onto any detainee who does not fully participate in his defense.

More nuanced approach

On the brighter side, the high court refused to overturn Faretta v. California, as the state of Indiana had sought. That 1975 case established the right of defendants to represent themselves so long as they made this choice "voluntarily and intelligently."

In addition, the ruling may whittle away at the unilateral view of competency espoused by the court in Godinez v. Moran, the only other Supreme Court case that has considered competence within the context of self-representation. In that 1993 opinion, written by Justice Clarence Thomas, the court engaged in convoluted reasoning to hold that no higher level of competency was required to waive counsel.

"There is no reason to believe that the decision to waive counsel requires an appreciably higher level of mental functioning than the decision to waive other constitutional rights," held the Court in Godinez. "The competence that is required of a defendant seeking to waive his right to counsel is the competence to waive the right, not the competence to represent himself."

In contrast, the Edwards opinion cites the empirical research conducted by the MacArthur group to assert that competency is not a single, unitary construct. Rather, understanding, reasoning, and appreciation of one's circumstances are separable aspects of functional legal ability, the court held.

We can only hope that this recognition of the complexity of competency, and the implicit endorsement of formal competency assessment tools such as the MacCAT-CA, signals an important shift in thinking.

In preparing this essay, I came across many good resources, some of which are listed here.

The ruling in Indiana v. Edwards is here. All of the various supporting and opposing briefs are available here and here. The American Psychiatric Association brief is here.

Erica Hashimoto's research on pro se defendants, Defending the Right of Self-Representation: An Empirical Look at the Pro Se Felony Defendant, 85 NC Law Review 432 (2007), is available for download here. An essay by her at the Concurring Opinions blog is here.

The New York Times, the Christian Science Monitor, and Legal Times have coverage of the ruling. Commentary is available at Scotusblog, Crim Prof blog, Simple Justice, the Legal Ethics Forum, and Court-O-Rama.

June 19, 2008

Mentally ill: No constitutional right to self representation

A few months ago, I blogged about an important case out of Indiana, pertaining to whether the mentally ill have a right to represent themselves in court. As many of you may recall, this Constitutional right led to the farcical and ironic spectacle of a railroad killer railroading himself straight to prison.

A few months ago, I blogged about an important case out of Indiana, pertaining to whether the mentally ill have a right to represent themselves in court. As many of you may recall, this Constitutional right led to the farcical and ironic spectacle of a railroad killer railroading himself straight to prison.That was Colin Ferguson (satirized by Saturday Night Live here). We have witnessed similar spectacles in other cases of floridly psychotic people acting as their own attorneys. Another example that I blogged about several times was Scott Panetti, who rambled insanely at his 1995 murder trial and tried to subpoena Jesus Christ, John F. Kennedy, and other dead people.

It's an easy conviction for the prosecution, of course. But it is hardly fair. And certainly not dignified.

In today's 7-2 ruling in the case of Indiana v. Edwards, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the mentally ill do not have the same constitutional rights as everyone else. Even though someone may be competent to stand trial with the help of a lawyer, a judge may force the defendant to accept an attorney if the trial might otherwise be a farce.

"The Constitution permits states to insist upon representation by counsel for those competent enough to stand trial ... but who still suffer from severe mental illness to the point where they are not competent to conduct trial proceedings by themselves," Justice Stephen Breyer wrote for the majority.

Proponents of allowing mentally ill defendants to represent themselves despite questionable understanding and judgment cite the Sixth Amendment's right to self-representation. Legal scholar Michael Perlin calls this argument a "pretextual" rationalization for injustice.

Today's decision involved Ahmad Edwards, a delusional schizophrenic man whom a trial judge ruled was competent to stand trial for a robbery-shooting but incompetent to represent himself. Edwards had an attorney but was convicted anyway, prompting his appeal. This ruling will likely reinstate his conviction.

The imposition of a higher standard for self representation than for other facets of competency to stand trial seems at odds with the high court’s earlier holding in Godinez v. Moran. Clarence Thomas, the author of that 1993 opinion, dissented in Thursday's ruling, as did fellow conservative jurist Antonin Scalia.

"In my view, the Constitution does not permit a state to substitute its own perception of fairness for the defendant's right to make his own case before the jury," Scalia said.

The full opinion in Indiana v. Edwards (07-208) is available here. USA Today has more here. My previous blog post on the case is here. Photo credit: afsilva, "The Railroad Ahead" (Creative Commons license).

May 9, 2008

Who will write the next DSM?

Or, at least, those are some of the BigPharma corporations with whom members of the task force charged with creating the 5th Edition of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders have contracts.

It shouldn't come as a surprise. But it ought to alarm the public, given BigPharma's enormous and growing influence in so many spheres of public life all around the world.

More than half of the experts involved in the previous edition of the psychiatric bible also had monetary relationships with drug makers, according to a Tufts University study. The percentage was up to 100 percent for experts working on certain severe mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia. (The New York Times story on that 2006 research is here.)

A just-published book, The Medicalization of Society: On the Transformation of Human Conditions into Treatable Disorders, has more on this construction of difference as illness. Trends that author Peter Conrad notes include the medicalization of "male" problems such as baldness and sexual impotence, and the pathologizing of children's behavior and appearance (short kids now have idiopathic short stature which requires synthetic human growth hormone).

Another new book, The Rise of Viagra, further documents the pathologizing of sexual variation, including an effort by BigPharma's spin doctors to create public hysteria and a new market for medicines to treat Female Sexual Dysfunction."

Meanwhile, as I've blogged about elsewhere, the sex offender industry is lobbying for new diagnoses to medicalize illegal sexual conduct, including "hebephilia" for men who are sexually attracted to teens, and "Paraphilia Not Otherwise Specified-Nonconsent" for men who rape.

Look for all these, and more, as possible candidates for the new and expanded DSM-V. Each edition of the DSM contains more diagnoses than its predecessor, and each diagnosis is supposedly treatable with meds. DSM-I (1952) listed 106 mental disorders, DSM-II (1968) had 185, DSM-III (1980) had 265, and DSM-IV (1994) has 357. That's an average of about 84 new diagnoses per edition, so the DSM-V should have 440 or more diagnoses.

Hopefully, this week's blog post by New York Times health writer Tara Parker-Pope about the conflict of interest signals that the public will be kept informed.

The consumer watchdog group Integrity in Science, a project of the Center for Science in the Public Interest, is also following the scent of money. See my Amazon book list, Critical Perspectives on Psychiatry, for other books on the DSM and the construction of illness.

March 27, 2008

Two major competency cases in court

- Should a higher level of competency be required for being one's own lawyer than for standing trial with a real lawyer?

- How competent must someone be in order for the state to kill him?

Competency to represent oneself

Although it was eclipsed by the OJ trial happening at the same time in Los Angeles, some readers may recall the farcical spectacle of Colin Ferguson's trial. Ferguson was the delusional man who opened fire on the Long Island Railroad, killing six people and wounding 19 more. After firing his prominent attorneys, he represented himself and presented a bizarre, delusionally based defense. He was found guilty, naturally, and received six consecutive life terms.

The Ferguson spectacle was enabled by the high court's 1993 opinion in Godinez v. Moran. Tom Moran was a severely depressed, suicidal defendant who waived the right to an attorney in a double murder case, pled guilty without presenting any evidence, and was promptly sentenced to die. The Supreme Court held that the same low standard of competency exists for all criminal proceedings.

Proponents of allowing mentally ill defendants to represent themselves despite questionable understanding and judgment cite the Sixth Amendment's right to self-representation. Legal scholar Michael Perlin, who just published an excellent book on competency, calls this argument a "pretextual" rationalization.

The competing positions were at the forefront of oral arguments before the U.S. Supreme Court yesterday in the case of Indiana v. Edwards. The case involves Ahmad Edwards, a schizophrenic man whom a trial judge ruled was competent to stand trial for a robbery-shooting but incompetent to represent himself.

The competing positions were at the forefront of oral arguments before the U.S. Supreme Court yesterday in the case of Indiana v. Edwards. The case involves Ahmad Edwards, a schizophrenic man whom a trial judge ruled was competent to stand trial for a robbery-shooting but incompetent to represent himself.The state of Indiana argued before the high court yesterday that allowing states to set their own, higher standards for self-representation ensures both fairness for accused individuals and the dignity of the courts.

Edwards' attorney countered that "the expressed premise of the Sixth Amendment and of our adversarial system generally is that the defense belongs to the accused and not to the state."

The high court justices were divided along predictable lines. Justice Stephen Breyer and Anthony Kennedy seemed concerned about people ending up in prison because they were too disturbed to represent their best interests at trial. But Justice Antonin Scalia said that's just too bad for them – if a defendant makes a poor choice, it is "his own fault."

A ruling is expected within the next few months.

Competency to be executed

The legal standard is much lower for competency to be executed. If you've got a basic understanding that you committed a crime and the state is going to kill you for it, you're good to go (to the Pearly Gates, that is).

That's the "Ford standard" set in the 1986 case of Ford vs. Wainwright, in which the Supreme Court ruled that executing a person who is severely mentally ill constitutes cruel and unusual punishment.

Last year, the highly polarized Supreme Court declined to clarify the somewhat vague Ford standard, issuing a 5-4 opinion on narrow procedural grounds in the closely watched Panetti v. Quarterman case (see my previous blog posts here and here; the opinion is here).

Last year, the highly polarized Supreme Court declined to clarify the somewhat vague Ford standard, issuing a 5-4 opinion on narrow procedural grounds in the closely watched Panetti v. Quarterman case (see my previous blog posts here and here; the opinion is here).Yesterday, a Texas court responded by affirming convicted killer Scott Panetti's competence to die. Indeed, said the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas, "if any mentally ill person is competent to be executed for his crimes, this record establishes it is Scott Panetti."

Panetti, who killed his estranged wife's parents, was found competent to stand trial after two jury trials on that issue. Unlike Ahmad Ewards, he was allowed to represent himself at his 1995 murder trial despite being floridly psychotic and delusional - and he's been regretting it ever since. During his trial, he rambled insanely and tried to subpoena Jesus Christ, John F. Kennedy, and other dead people.

"The record of Panetti's competency hearings and trial is not pretty," the appellate court conceded. "For better or worse, however, the issues of Panetti's competence to stand trial and his insanity defense have been tried, appealed, reviewed in state and federal habeas proceedings, and conclusively put to rest. Panetti is not permitted to relitigate these arguments in his proceedings under Ford."

The court’s 62-page opinion is interesting reading. It reviews the facts of the case, the exhaustive history of appeals, and the expert witness testimony of numerous well-regarded forensic experts called by both sides. The case even involved expert testimony by a forensic psychiatrist and neurologist, Dr. Priscilla Ray, on the science behind competency opinions, that is, "the extent to which psychiatric science can assist the Court in assessing competence to be executed, particularly with regard to the concept of rational understanding."

In discussing Panetti's "rational understanding" of his situation, the court also contemplated evidence suggesting that Panetti was exaggerating his schizophrenic disorder to avoid the needle. Yesterday's opinion cited the results of widely used tests of malingering, including the Structured Inventory of Reported Symptoms (SIRS) and Green's Word Memory Test (WMT).

At the end of the day, after reviewing all of the evidence, the Court held:

"Panetti is seriously mentally ill…. While the extent to which Panetti has been manipulating or exaggerating his symptoms is unclear, it is not seriously disputable that Panetti suffers from paranoid delusions of some type… However, it is equally apparent … that [his] delusions do not prevent him from having both a factual and rational understanding that he committed [the] murders, was tried and convicted, and is sentenced to die for them…. Panetti was mentally ill when he committed his crime and continues to be mentally ill today. However, he has both a factual and rational understanding of his crime, his impending death, and the causal retributive connection between the two."The ruling can be found HERE. National Public Radio has coverage and commentary here. A 28-minute video, "Executing the Insane: The Case of Scott Panetti," is available here. An essay by Yale scholar Steven Erickson entitled "Minding Moral Responsibility," which discusses the Panetti case, is available here. The Indianapolis Star has more coverage of Indiana v. Edwards.

Hat tip: Steven Erickson

February 8, 2008

Can insane killer inherit mother's estate?

That's the issue in a case that may set legal precedent in Washington.

Joshua Hoge, a 37-year-old man with schizophrenia, has been locked up on the forensic unit at Western State Hospital (where I happened to do my forensic postdoctoral fellowship) since being found not guilty by reason of insanity in the stabbing death of his mother and half-brother in 1999. Hoge was experiencing a so-called Capgras delusion at the time, believing identical-looking impostors had replaced his family members.

We're not talking chump change.

After the death of Hoge's mother, her family won $800,000 because two days before the killings a public health clinic had refused to give Hoge his antipsychotic medication. The family wants the money to go to the deceased woman's third son, who is also mentally ill and in need of lifelong care.

In some U.S. states, the question of whether someone found not guilty by reason of insanity can inherit from the estate of his or her victim has been decided by case law. Not so in Washington.

The legal issue here is whether the killings were "willful" and "unlawful," which would preclude Hoge from getting the money under Washington's "Slayer Statute." Hoge's attorney is arguing that the killings were not "unlawful" because Hoge was found not guilty. In a preliminary ruling, an appellate court held that while Hoge's mental illness absolved him of criminal responsibility, the killing was still unlawful. Whether the killing was "willful" remains to be decided.

The case has been remanded to the trial court in King County for a determination of "the degree to which Hoge's delusion prevented him from forming the intent to kill." A court date has not been set.

The opinion in Estate Of Pamela L. Kissinger v. Joshua Hoge is here. The Seattle Times has news coverage.

Hat tip: Andrew Scarpetta

February 1, 2008

Violence among psychiatric patients

First, and probably most controversial, is a heated debate looking back at the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study, which some cite as proof that discharged psychiatric patients are no more dangerous than anyone else. Facing off are the big names - John Monahan, Hank Steadman, E. Fuller Torrey, and Jonathan Stanley.

Next, there's a review of all empirical studies of violence and victimization among people with severe mental illnesses in the United States since 1990, along with a discussion of the public health implications, by the esteemed Linda Teplin and colleagues.

Then, there's a very practical article on assessing risk for violence by psychiatric patients, aptly entitled "Beyond the 'Actuarial Versus Clinical' Assessment Debate."

And, there's more - online here. The lead editorial and the abstracts for each article are free, but the full articles require a subscription, unfortunately.

January 19, 2008

Daryl Atkins, Lindsey Lohan, and the Cuckoo's Nest

Daryl Atkins' sentence commuted

On Thursday, more than five years after Daryl Atkins made legal history with a U.S. Supreme Court ban on executions of the mentally retarded, a judge commuted his death sentence to life in prison.

On Thursday, more than five years after Daryl Atkins made legal history with a U.S. Supreme Court ban on executions of the mentally retarded, a judge commuted his death sentence to life in prison.The reprieve came for reasons that few would have guessed during the ever twisting, nearly 12-year course of the case, which had focused largely on Atkins's mental limitations. Instead, it resulted from an allegation that prosecutors suppressed evidence prior to Atkins's murder trial in 1998.

The Washington Post has the story.

Cuckoo’s Nest still crazy

Most people know Oregon State Hospital only for the movie that it was based on, 1975's award-winning "One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest."

Most people know Oregon State Hospital only for the movie that it was based on, 1975's award-winning "One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest."Well, it looks like Nurse Ratched never retired. A U.S. Justice Department report issued Wednesday cites numerous horror stories, including patient-on-patient assaults, outbreaks of infectious diseases, and a patient being held in seclusion without treatment for a year.

State officials said things have improved since the 2006 investigation, and that conditions at the crumbling, century-old psychiatric hospital are a symptom of years of neglect and underfunding of the entire public mental health system.

The Oregonian has the story. Also online are the federal report and a Pulitzer prize-winning series from the Oregonian, "Oregon’s Forgotten Hospital."

Better news from the other side of the country -

No more "hole" for mentally ill prisoners

On Tuesday, New York's legislature approved a landmark law to remove severely mentally ill prisoners from solitary confinement in prison and place them in secure treatment facilities.

Prisons will also be required to conduct periodic mental health assessments of all prisoners in segregated or special housing units known as SHUs, where they are typically locked up for 23 to 24 hours a day.

New York has had more prisoners in segregated units for disciplinary purposes than any state. Confinement in tiny cells for 23 to 24 hours a day is known to seriously worsen psychiatric illnesses, which are suffered by large numbers of prisoners. (See my online essay on segregation psychosis for more on this topic.)

The governor is expected to sign the law, paving the way for construction of the new residential mental health units.

Newsday and the Poughkeepsie Journal have more.

Online registry for domestic violence?

In another example of the potentially endless expansion of symbolic laws, a California lawmaker has introduced a bill to develop an online database of domestic violence offenders, modeled after the popular sex offender databases.

Although the San Jose Mercury News is reporting this as the first such law proposed in the United States, I blogged last June about a similar effort in Pennsylvania.

Whatever state gets to it first, it's just another misguided, tough-on-crime attempt to get votes, in my opinion. Why?

First, it is costly and likely to divert funds from existing domestic violence programs that are already facing cutbacks. (This week's Boston Globe, for example, reports that women are waiting weeks for scarce beds in battered women's shelters, forcing them to return to their abusers and face greater danger.)

Second, as mentioned by a spokeswoman for the California Partnership to End Domestic Violence, a victims' advocacy group, women who have been wrongfully convicted of assaulting their abusers will likely find their names on the registry, creating further victimization.

Third, and most important in my opinion, is that these registries do more harm than good. They don't stop crime. All they do is stigmatize. The more they expand, the harder it is for people to get jobs, find housing, and be rehabilitated. And the number of candidate pools is endless: Drug offenders. Drunk drivers. Terrorists. Antiwar protesters. Traffic light violators.

The Mercury News has the story.

But what about Lindsey Lohan?

Oh yes, since I've been doing the celebrity blog thing lately, reporting on the Britney Spears-Phillip McGraw controversy, I must not neglect the innovative sentence handed down on Thursday to Ms. Lohan.

Oh yes, since I've been doing the celebrity blog thing lately, reporting on the Britney Spears-Phillip McGraw controversy, I must not neglect the innovative sentence handed down on Thursday to Ms. Lohan.The L.A. courts have a program to show drivers the real-life consequences of drinking and driving. So as part of her sentence for misdemeanor drunk driving the 21-year-old actress must work at a morgue and a hospital emergency room for a couple of days each. I think it's a great idea. And maybe it will give her fodder for new acting roles. I'm rooting for her to get past all of this mess and get on with her promising career.

The Associated Press has the story.

December 6, 2007

New Report: Mentally ill in Florida's legal system

The report follows media exposes detailing the plight of the mentally ill trapped in Florida's legal system. Mentally ill people often end up homeless and with substance abuse problems, leading to a revolving door of incarceration for minor nuisance offenses. The report recommends reforms to link the mentally ill to services that will reduce recidivism, and to improve the handling of mentally ill individuals in the juvenile, foster care, and child protective systems.

The Council of State Governments Justice Center in New York chose Florida as one of seven states to address the national crisis of the mentally ill in the legal system. The 170-page report is supposed to be the first step in a major overhaul that will include additional training for members of the judiciary. The report's massive title gives a hint of the massiveness of the project: "Mental Health: Transforming Florida's Mental Health System: Constructing a Comprehensive and Competent Criminal Justice/Mental Health/Substance Abuse Treatment System: Strategies for Planning, Leadership, Financing, and Service Development."

The report is available online. The National Institute of Corrections has a number of related documents online on the crisis of mental illness and substance abuse in the U.S. criminal and family court systems.

November 12, 2007

Do mental health courts work?

Many communities have created specialized mental health courts in recent years. However, little research has been done to evaluate the criminal justice outcomes of such courts. This study evaluated whether a mental health court can reduce the risk of recidivism and violence by people with mental disorders who have been arrested. In this study, 170 people who went through a mental health court were compared with 8,067 other adults with mental disorders booked into an urban jail during the same period. Statistical analyses revealed that participation in the mental health court program was associated with longer time without any new criminal charges or new charges for violent crimes. Successful completion of the mental health court program was associated with maintenance of reductions in recidivism and violence after graduates were no longer under supervision of the mental health court. Overall, the results indicate that a mental health court can reduce recidivism and violence by people with mental disorders who are involved in the criminal justice system.The report, “Effectiveness of a mental health court in reducing criminal recidivism and violence,” is by DE McNiel and RL Binder of the Langley Porter Psychiatric Institute in San Francisco. It was published in the September 2007 issue of the American Journal of Psychiatry (Volume 164 Number 9). For a reprint, contact the authors at dalem@lppi.uscsf.edu.

November 9, 2007

Claim in 15-year-old girl's stabbing will highlight prison failures

The family of a 15-year-old San Francisco girl who was severely stabbed by a paroled prisoner plans to file a claim against prison officials next Monday.

The family of a 15-year-old San Francisco girl who was severely stabbed by a paroled prisoner plans to file a claim against prison officials next Monday.Scott Thomas, who was accidentally paroled from San Quentin Prison due to a clerical blunder, had a documented history of bipolar disorder and was flagged by guards as needing treatment that he never received, two prison clinicians secretly told the San Francisco Chronicle. He randomly stabbed the 15-year-old girl and a man who came to her rescue at a bakery. After his arrest, he mumbled, "I'm taking on the world" before breaking into incoherent song, according to a police report.

Accidental releases are lawsuits waiting to happen. And it is lamentable when prisoners slip through the cracks of psychiatric treatment. But these issues miss the bigger picture: Thomas, a repeat theft offender who was only violent when in prison, was released to the streets straight out of solitary confinement.

Recipe for violence

Imagine being locked up all by yourself in a windowless cement box no bigger than a bathroom. Imagine being all by yourself in that box for months on end. (Thomas was only in "the hole" for four months; some prisoners in supermax prisons are kept in isolation for decades).

As depicted in the 1973 Steve McQueen film Papillon, based on a true story about an escape from a prison colony in French Guiana, it doesn't take long to have a mental breakdown under these conditions. Just a couple of days of solitary confinement with sensory deprivation can trigger psychotic hallucinations. Ellectroencephalogram research shows that after only a few days in solitary confinement, prisoners' brain waves shift into a stuporous, delirious pattern.

Now imagine that you are locked up in that windowless little box when you are already mentally ill and tormented by demons inside of your head.

Many prisoners, such as Thomas, are already fragile and unstable. They are even more prone to psychiatric breakdown than are healthy people who did not undergo severe childhood trauma. Putting mentally ill prisoners in solitary confinement is like putting an asthmatic person in a room with no air, as a federal judge once put it.

When I worked in a segregation housing unit (SHU) for the mentally ill, I saw these effects first-hand. After a short time on the unit, many prisoners began to babble incoherently or to lie semi-comatose in a fetal ball. They screamed and yelled and hurled excrement and urine through the narrow slits in their cell doors. They tried to kill or mutilate themselves.

Further demolishing the psyches of these vulnerable prisoners is not only cruel, it is also a surefire recipe for community endangerment when they get released, as most eventually will. Some prison administrations have realized that discharging convicts straight from the hole to the streets is a dangerous practice. Oregon, for example, integrates prisoners back into the prison mainstream through classes and jobs before releasing them.

Despite the demonstrated, permanent harm to prisoners' psyches – which ultimately translates into harm to vulnerable victims such as the 15-year-old San Francisco girl – solitary confinement is on the rise. From 1995-2000, its use rose by a dramatic 40%, surpassing the overall prison population rise of 28% during that period.

"We have to ask ourselves why we're doing this," psychiatrist Stuart Grassian, a Harvard professor and expert on segregation psychosis, told Time magazine. (For more on Grassian and his research, see my web page on "segregation psychosis.")

Wouldn’t it be great if rationality and community safety prevailed, and this barbaric practice was put to rest? Perhaps more lawsuits like this family's will get the attention of prison officials.

National Public Radio has an excellent, three-part series by Laura Sullivan on solitary confinement. In one episode, she spends the day with Daud Tulam, a New Jersey man adjusting to life on the outside after 18 years in solitary confinement. Tulam struggles with the common everyday things that we all take for granted, such as smalltalk, noise, and mere human companionship.

November 2, 2007

Do childhood mental disorders cause adult crime?

The past ten years have witnessed a surge of research on adolescent offenders with mental disorders. The research shows that youths with delinquencies often have mental disorders, and youths with mental disorders are at greater risk of delinquencies. This 'overlap' of the two populations is a good deal less than a majority when examined as a proportion of all delinquent youths or of all youths with mental disorders. Yet it is substantial, especially among the subset of delinquent youths in juvenile justice secure facilities, where about one-half to two-thirds meet criteria for one or more mental disorders.The essay continues here.

These findings have focused attention on the implications of public child protective and mental health services for criminal conduct. Is the national crisis in child community mental health services contributing to delinquency and causing the juvenile justice system to become the dumping ground for youths who are inadequately served? Can we reduce delinquency by providing better resources for responding to youths with mental disorders?

The important Smoky Mountains study, "Childhood Psychiatric Disorders and Young Adult Crime: A Prospective, Population-Based Study," by William E. Copeland, Shari Miller-Johnson, Gordon Keeler, Adrian Angold, and E. Jane Costello, is also available online. Here is the Abstract:

While psychopathology is common in criminal populations, knowing more about what kinds of psychiatric disorders precede criminal behavior could be helpful in delineating at-risk children. The authors determined rates of juvenile psychiatric disorders in a sample of young adult offenders and then tested which childhood disorders best predicted young adult criminal status. A representative sample of 1,420 children ages 9, 11, and 13 at intake were followed annually through age 16 for psychiatric disorders. Criminal offense status in young adulthood (ages 16 to 21) was ascertained through court records. Thirty-one percent of the sample had one or more adult criminal charges. Overall, 51.4% of male young adult offenders and 43.6% of female offenders had a child psychiatric history. The population-attributable risk of criminality from childhood disorders was 20.6% for young adult female participants and 15.3% for male participants. Childhood psychiatric profiles predicted all levels of criminality. Severe/violent offenses were predicted by comorbid diagnostic groups that included both emotional and behavioral disorders. The authors found that children with specific patterns of psychopathology with and without conduct disorder were at risk of later criminality. Effective identification and treatment of children with such patterns may reduce later crime.

October 29, 2007

ABA calls for death penalty moratorium

The American Bar Association today released findings of a three-year study on state death penalty systems and called for a nationwide moratorium on executions. Currently, more than 3,000 people are awaiting the needle, the chair, or the gallows.

The American Bar Association today released findings of a three-year study on state death penalty systems and called for a nationwide moratorium on executions. Currently, more than 3,000 people are awaiting the needle, the chair, or the gallows.In its detailed analyses of death penalty systems in eight U.S. states, the report highlights "key problems" that make the current system unfair, including racial disparities (more than 4 out of 10 death row prisoners are black, according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics), inadequate defense services for indigent defendants, and irregular processes for clemency review. The report also documents serious problems with evidence collection, preservation, and analyses; state crime laboratories are systematically underfunded and look nothing like those on television's CSI.

Of relevance to forensic psychology, the ABA's investigatory committee found that many states do not ensure that lawyers who represent mentally ill and mentally retarded defendants understand the significance of their clients' mental disabilities. In addition, jury instructions do not always clearly distinguish between the use of insanity as a legal defense and the introduction of mental disability evidence to mitigate capital sentencing.

Prosecutors and death penalty supporters are calling the study biased, saying many of the attorneys on the state investigation teams are death penalty opponents.

The full report is available online through CNN.

Chart: Capital Punishment, 2005, Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice.

October 22, 2007

Book Recommendation: The Center Cannot Hold

If you're deciding what to read next, I strongly recommend Elyn R. Saks' The Center Cannot Hold: My Journey Through Madness. I guarantee you won't forget it soon.

Saks is an acclaimed professor of law and psychiatry. She also struggles with severe symptoms of schizophrenia. She risked her reputation in academia in order to give hope to others like herself, and to counter the negative stereotypes about mental illness held by both the general public and mental health professionals:

"I wanted to dispel the myths ... that people with a significant thought disorder cannot live independently, cannot work at challenging jobs, cannot have true friendships, cannot be in meaningful, sexually satisfying love relationships, cannot lead lives of intellectual, spiritual, or emotional richness."The topic is inherently compelling, and Saks masterfully describes what it is like to be tormented by inner demons, to be forcibly restrained on a hospital bed, to require medications that alter one's mental state and can cause horrific, irreversible side effects. She articulately describes her years of talk therapy, in which she came to understand the functional underpinnings of her psychotic thoughts, for example in warding off feelings that would have been consciously threatening.

I enjoyed her dry humor in highlighting the condescension and absurdities of the mental health system. In one case she reviewed during a legal internship, the patient was restrained because he refused to get out of bed. In another case, a young man was deemed delusional because he continually spoke with "imaginary lawyers" - who turned out to be none other than Saks and her colleague.

For years, in order to excel, Saks had to lead a double life. Swirling around her, constantly threatening, was the stigma of mental illness. While writing an academic paper on restraints, she asked a professor, "Wouldn't you agree that being restrained is incredibly degrading, not to mention painful and frightening?" With a kind and knowing look, the professor responded: "These people are different from you and me. It doesn't affect them the way it would affect us."

This book is especially important reading for mental health professionals in the United States, where medication reigns supreme (it has become practically taboo to recommend psychotherapy for severe psychosis, despite ongoing research establishing its efficacy) and coercion often trumps choice. Saks contrasts her experience of being hospitalized in the United States with her experience in England, where restraints have not been in widespread use for more than 200 years. In doing so, she gives us a deeper appreciation of the trauma induced by coercive and sometimes brutal treatment.

"The Little Engine that Could" is what her close friend Steve Behnke calls her, referring to her indomitable spirit even in the face of hospital clinicians' dire predictions about her future.

I highly recommend this courageous and brilliant memoir.

A 45-minute video of Saks' talk at this year's American Psychological Association convention is available online at her personal website. Other books by Saks include Refusing Care: Forced Treatment and the Rights of the Mentally Ill (2002) and Jekyll on Trial: Multiple Personality Disorder and the Criminal Law (1997).